Relaxation techniques can be used regularly to help reduce pain, tension and stress.

‘Learning to breathe and release tension properly has changed the way I face cancer. You become better at monitoring your body. I use my breath to manage my pain and monitor how I’m going day to day within myself. I guess it gives me a sense of control over it.’

TOM, 65

‘Cancer is humbling because it makes you realise how little you really control. I ran around like a self-important guard dog for years, yapping and jumping and fretting, thinking I really made things happen. Cancer plucks you out of that illusion and drops you in a deep and unknown space … The only way out is to dive into your inner self and start some realignment. It teaches you that the only reality is the inner life, from which all outer manifestations arise.’

ANNA, 42

The ongoing uncertainty and lack of control over melanoma isn’t easy, even when we are healthy. A melanoma diagnosis confronts us with our own mortality and the limitations of human control. It can highlight our vulnerability and fragility.

Processing grief and loss

The process of adjusting to melanoma hardly ever progresses in a straight line – we can cycle through many ways of thinking, feeling and coping. Grief, the natural response or reaction to loss, can be emotional, mental, physical, spiritual or relational. Grief is an emotion, but also a way of coping that is healthy and appropriate to a diagnosis of cancer. The grieving experience is different for everyone, but it is an important part of life. Grieving is rarely linear, but complex and takes time. Grieving is also active – you need not feel powerless or alone. Accessing professional support is recommended to help process your grief. Relaxation and self-soothing are vital in coping with grief, cancer, and pain.

Nurturing the nervous system

It is important to have ways to deal with cancer, pain and stress that reduce muscle tension and counter the ‘fight–flee–freeze’ response. The body has a system that does just that: the parasympathetic nervous system or relaxation response. This response was named by Harvard Medical School physician Herbert Benson. In the 1960s, he pioneered what has become known as mind–body medicine – recognition that the state of the mind and emotions influences the health of the body. Benson’s work showed that, during meditation and some other relaxation activities, physiological changes occur. The body uses less oxygen, breathing and heart rate become slower, and high lactate levels and blood pressure (often associated with stress and anxiety) are reduced. Benson proposed that, in the same way the stress response is essential to survival, the relaxation response is an adaptation to survival – that one counteracts the effects of the other.

The good news is that we can nurture the nervous system by learning to relax. We can successfully release tension and quieten the body by harnessing this adaptive response. Learned relaxation, in whatever form it takes, is a vital initial step in managing cancer pain and the stress response.

Does relaxation really work for cancer pain?

Relaxation is a powerful way to counteract the effects of the fight–flee–freeze response, particularly in people with melanoma. Medicines often don’t completely relieve cancer pain, despite over half of people diagnosed with cancer suffering from pain. Relaxation, mind–body techniques, meditation and mindfulness-based strategies (in combination with medication) all improve pain severity, pain-related distress, anxiety, stress, depression and quality of life in people living with a variety of cancers and pain.

Meditation in modern-day complementary health care has been used in ancient systems such as yoga for thousands of years. Meditation practices have been found to be associated with pain relief – they have a painkiller effect by acting on the stress response regions of the brain.

Nurturing relaxation

Relaxation techniques can be used regularly to help reduce pain and tension. You can also use them to reduce pain when you are experiencing increased pain or stress. A simple breathing technique can help you before a stressful situation such as going to an oncology appointment or treatment session. It can increase your sense of calm and control.

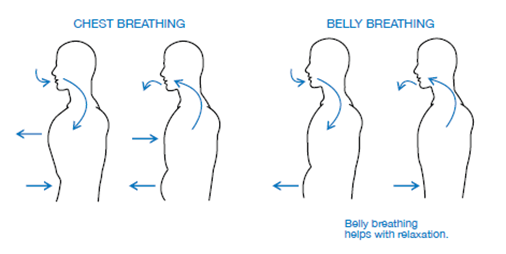

Many of the most powerful techniques that help process grief or reduce cancer pain are based around breathing and muscle relaxation (body awareness), or a combination of these approaches. Many people also try meditation to help them relax. There are many methods you can use to foster the relaxation response. All involve a central anchor – the breath. Below are two simple techniques.

Meditation technique – Belly Breathing

- Choose a quiet place where you will not be disturbed. Find a position that is comfortable and allows the spine to feel long, aligned and maintaining a natural curve, whether sitting or lying. You might like to close your eyes or darken the room, to reduce distractions.

- Place one hand on your upper chest and one hand on your belly, just below the rib cage.

- Take a few long, deep breaths, lengthening your out-breath. Pay attention to your breathing. Remember that short, shallow breathing is common with cancer and pain, but it is an unhelpful response to stress.

- As you breathe in slowly through your nose, allow your belly to expand; as you breathe out, allow your belly to relax. Imagine the air slowly filling your lungs and body as you breathe in and then flowing out again as you breathe out.

- If your hands are still in position, become aware of your hand rising as your belly expands like a balloon. The hand on your chest should remain as still as possible.

6. When you notice your pain or when your mind has wandered or been distracted, acknowledge it, accept that this is what the mind tends to do, and then bring your attention gently back to your breath. At first, this technique can be tiring and make you feel light-headed. Have confidence that it will become easier and automatic with continued practice. See if you can increase to 5–10 minutes, three or four times each day.

Pursed-lip breathing

Cancer alongside the stress response might make it difficult for you to breathe. If you are about to receive some treatment you might feel an internal sensation of panic, which in turn heightens your perception of threat. Your stress response can be activated, which can cause you to breathe more rapidly and shallowly through the mouth, and worsen other unpleasant sensations such as panic, pain and increased heart rate. This can then begin a cycle of catastrophic thoughts such as not being able to breathe or the pain never stopping. Over time, this can increase your perception of threat even further. The good news is that a certain breathing technique can help with cancer pain and other symptoms of cancer, such as breathlessness. Pursed-lip breathing is an important way to help with anxiety and breathlessness. It is also useful if you are feeling nauseous or tired.

Meditation technique

- Find a comfortable position, keeping your shoulders relaxed, your arms and fingers loose.

- Focus on breathing in gently and slowly through your nose, without any force or effort. Try to move each breath into your belly, so you can feel your waist area expand as you breathe in.

- Count, ‘in, one’ in your head as you breathe in through your nose. Imagine as you breathe in that you are smelling a beautiful fragrance.

- Focus on breathing out gently and slowly through your mouth, with lips pursed. Imagine as you breathe out that you are cooling a hot drink. This will make your outbreath longer. Count, ‘out, one, two’ in your head as you breathe out.

- This method may seem awkward at first, but it eases laboured breathing, which is especially important during a pain episode. When your muscles are relaxed, breathing is easier.

Sometimes, seeking clinical psychology support as an evidence-based approach to managing adjustment to melanoma, grief, and cancer pain is vital. Don’t be afraid to reach out to the Clinical Psychology Service at MIA.

Written by Dr Skye Dong, Senior Clinical Psychologist. This is an edited excerpt adapted from her new book, The Cancer Pain Book, 2022 by Professor Melanie Lovell, Rebecca McCabe, Dr Skye Dong, and Professor Philip Siddall.